Relative Humidity, Temperature, and Moisture Content

Relative Humidity, Temperature, and Moisture Content

This is Part 2 of a two-part series on cellulose insulation and moisture. Cellulose insulation is a hydrophilic material, meaning that absorbs moisture readily. Under certain conditions condensation dampens cellulose insulation causing permanent damage due to shrinking, slumping, and very slow drying.

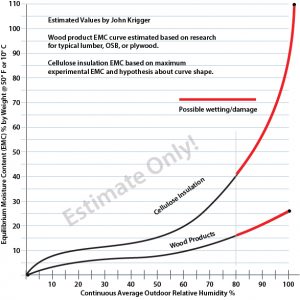

Moisture adsorption into a hydrophilic material, expressed as equilibrium moisture content (EMC), is directly proportional to the relative humidity of the air around the material. The EMC is also inversely proportional to the dry bulb temperature. These relationships between EMC, RH, and temperature are important, especially for hydrophilic materials in regions with high humidity.

Humid Climates and the Danger of Condensation

I estimate that there are at least 100 cities and towns on the eastern seaboard, Gulf Coast, and coastal Pacific Northwest that have average annual relative humidities between 78% and 82%. We should suggest caution in installing cellulose wall insulation in these areas.

Various laboratory studies report cellulose insulation EMCs of up to 140% water by weight at RHs of up to 95%. At 80% average Rh, aged OSB has 30% moisture content and wood has around 17%, according to research. I would estimate that cellulose insulation has 30% to 60% moisture content under these same conditions. That means that dense-packed cellulose at 4 pounds per cubic foot actually weighs 5.2 to 6.4 pounds per cubic foot including the water and water vapor.

Mechanisms of Wetting

I agree that cellulose insulation won’t get wet during most normal conditions. However buildings last a long time and there’s ample opportunity for unusual humidity and temperature conditions that could cause the cellulose insulation to become wet and suffer permanent damage.

No designer or computer software can control the outdoor relative humidity. If outdoor RH remains high for a long time, the building materials absorb moisture. The whole building absorbs moisture depending on the relative humidity, temperature, and rainfall. Many building designers focus only on controlling indoor relative humidity and minimizing airflow between the indoors and outdoors. Air leakage through the wall isn’t the only way that the wall can absorb moisture. High outdoor relative humidity will absolutely affect the EMC of cellulose insulation.

Possible Wetting Conditions

- Consider a wet fall where snow or heavy rain has saturated the ground. October is very humid and rain has dampened the cladding. The sun pushes the moisture through the cladding into the cellulose. Then the temperature drops below freezing saturating the cellulose insulation with condensation and even ice.

- And then there’s fog. Consider relative humidity of between 75% and 100% with millions of water droplets per cubic foot. Consider a ventilated roof cavity insulated with cellulose insulation. The ventilating foggy air could be 90% RH with fog that deposits water droplets in the cool roof cavity.

- Or consider a damp location. Ketchikan Alaska has over 100 inches of rainfall and a very high relative humidity. Mold grows on Tyvek during construction and most builders use plywood instead of the more vulnerable OSB for sheathing. Builders in Ketchikan know better than to use cellulose insulation.

Most studies of wetting that I’ve read focus on the structural sheathing because it has the essential function in holding the building together. I haven’t seen any experimental results on measurements of the moisture content of cellulose-insulated walls in humid conditions. However, I fear that there are tons of wet cellulose insulation in these humid climates.