This is a two-part blog about hygric buffering, cellulose wall insulation, and moisture problems in high-performance buildings.

Why not to install cellulose insulation in deep wall cavities

Cellulose shrinks, slumps, and dries very slowly after wetting. Deep wall cavities are have more risk because the outdoor side of the wall is colder than shallower cavities. Voids left by the shrinking and slumping insulation create more room for humid air in the wall cavity. A vapor retarder can’t ensure that cellulose wall insulation won’t get wet. Of course, fiberglass and rock wool insulation also get wet. However they don’t adsorb much water vapor. When the water vapor condenses in rock wool or fiberglass insulation, the water falls out by gravity, leaving the insulation undamaged. However, mold can grow in fiberglass batts, but hardly ever in cellulose, in my experience.

What is hygric buffering?

My first exposure to hygric buffering was reading research papers that discussed the possibility that hygric buffering could control indoor relative humidity. These papers hypothesized that hygric buffering could substitute for some of the electricity-consuming dehumidification provided by mechanical ventilation or dehumidifiers.

Builders eliminated vapor barrier in the ceilings of some buildings here in Montana 30 years ago to substitute for ventilation. That hygric buffering didn’t work so well. Cellulose attic insulation got wet, shrunk, and hardened throughout these attics.

Many building professionals still believe that cellulose insulation provides humidity control and condensation protection. Hygric buffering adsorbs and distributes moisture, they claim, protecting both the cellulose insulation and building materials around it from condensation. Although I believe this can happen, I also believe that cellulose will get wet at a particular and unknown equilibrium moisture content (EMC).

WUFI and hygric buffering

WUFI is a software program distributed by the Fraunhofer Institute in Germany. Passive House builders swear by WUFI nd seem to think that WUFI analysis has miraculous powers to protect buildings from condensation. When I ask questions about cellulose insulation and the possibility of wetting, the WUFI users assure me that WUFI proves it won’t happen.

Realistically, WUFI can’t stop cellulose from getting wet. High-performance builders and building scientists do mention wetting and drying in walls. However, they don’t often acknowledge that wetting damages cellulose insulation. Almost all of the research on wall wetting focuses on the wall sheathing and not the insulation.

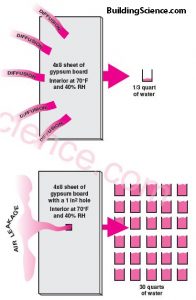

Air leakage & water-vapor diffusion

Joe Lstiburek created a famous illustration showing that air leakage is usually a more important factor in wall moisture compared to vapor diffusion. That illustration made many building professionals think that vapor diffusion was a negligible factor. Joe didn’t mean that. Maybe WUFI now perpetuates that belief that water-vapor diffusion is a negligible factor in wetting.

Can someone answer the following questions about hygric buffering with reference to cellulose insulation?

- What is the benefit of hygric buffering?

- Is hygric buffering an important design consideration?

- How do we achieve optimal hygric buffering without condensation?

- Are the benefits of hygric buffering why builders choose cellulose insulation for walls?

Equilibrium moisture content (EMC) of building materials is even more important than vapor diffusion. In my next post we’ll discuss what affects EMC. In the meanwhile, read this article about a fat wall failure in Vermont in the Journal of Light Construction.

Charles Buell wrote this comment:

“I built many dense pack cellulose insulated houses in the Oswego/Syracuse NY area in the early 80’s—ten inch truss type walls and I can tell you if the insulation is installed properly no settlement occurs. In that climate, obviously good vapor barriers are required on walls and ceilings. In one house (my own) I installed a 2′ square glass panel at the top of one wall bay to monitor settlement due to this wrong information. 4 years later I covered it over with drywall. When I took off the glass the insulation was dry and still trying to expand into the space. It is a total myth that properly installed cellulose settles or represents a moisture issue in thick wall installations.”

I’m not saying that cellulose wall insulation necessarily gets wet or settles. I’m sure there are many walls that are dry and haven’t settled a bit. However, I believe that the risk wetting and settling are too high, except for new walls in dry climates.