A Proposal for Energy-Conservation Loans

The following is a proposal for a revolving loan fund that a State, municipality, or utility organization could administer. This proposal resulted from a long conversation between John Krigger and Gary Klien, who at the time worked for the California Energy Commission.

Model: The Nebraska Revolving Loan Fund

Nebraska’s State revolving conservation loan fund is an example of a successful public-benefit loan program. The Nebraska Energy Office capitalized this loan program in 1991, using oil-overcharge funds. The Nebraska revolving loan fund was initially capitalized at approximately $30 million but received an additional $11 million through ARRA funding. It has generated around $200 million in conservation loans in 19 years. Loans are available to residential, commercial and industrial customers at rates ranging from 2.5 – 5%. The payback term ranges from 5 – 15 years. Only improvements to existing buildings that are at least five years old are eligible for loan assistance. Maximum loan amounts range from $10,000 to $175,000 depending on the type of loan sought. Loan applicants first approach a financial institution, which approves the project on financial terms before contacting the Nebraska State Energy Office (NSEO) for its approval. The State then purchases either 50% or 75% of the loan at 0% interest so the loan customer pays only 2.5 – 5% interest. All qualifying work must be completed within five months of NSEO’s commitment of funds. The bank collects its principle and interest along with the State’s principle and then repays the State’s principle to the revolving fund quarterly. Although the loan program is successful at generating economic activity, its energy-saving performance is unknown because of the lack of measurement.

Revolving Loans and the Modern Benefit Fund

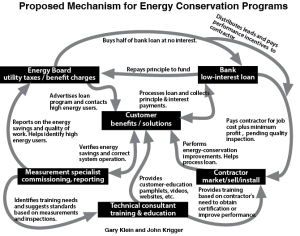

Unlike the oil-overcharge-capitalized Nebraska fund, public-benefit funds being created by deregulation have a continuous revenue flow. A State or regional power administration could manage the fund, feeding a portion of the public-benefit revenues into a revolving loan fund and another portion into advertising, marketing, administration, measurement, performance incentives, technical assistance, and auditing. If the fund were allowed to accumulate beyond what was being lent, interest on the unused fund could be used to counter inflation and pay expenses. Listed below are the possible players in the new energy market, created by the loan program.

Energy board (EB)

The energy board (EB) is a government or private agency that invests the tax revenue. The EB advertises and promotes the loan program and generates leads for qualified contractors with the help of the measurement specialist in identifying high users. The EB buys half of the conservation loan from the bank at no interest, cutting the bank’s interest rate in half for the customer. The EB rewards actual savings by measuring results and paying graduated incentives. Necessary repairs and health & safety improvements may be included in the loan as long as an acceptable energy savings-to-investment ratio is maintained.

Utility customer

The utility customer learns about the loan program through the EB’s advertising and marketing. The customer becomes more aware of possibilities for energy and resource conservation through specific information produced by the technical consultants. The customer decides to buy because of the benefits: low-interest loan, qualified contractors, savings measurement, and quality inspection. The customer chooses a contractor based on a proposal, the contractor’s reputation, and performance information available from the board.

Contractors

Contractors register with the EB by presenting certification and proof of experience in performing specific energy-conservation measures. Contractors seek training and certification as needed from the technical consultants. The EB supplies the contractor with qualified leads. The contractor sells the job and works with the bank to secure the customer a low-interest loan. The contractor risks earning a minimum profit if no energy savings result. The contractor’s record-keeping meets the auditor’s standards for separating job cost from profit. Reimbursement of job cost is dependent on quality inspection, and quarterly incentive payments (profit) are dependent on energy savings and these incentives must be high enough to make the best contractors interested.

Bank

Banks qualify loan applicants, process loans, collect principle and interest repayments, and repay principle to the revolving loan fund. The bank determines interest rate of the loan based on customer creditworthiness and competition from other banks. Interest should range from four to eight percent. The bank’s benefit is increased loan volume.

Measurement specialists (MSs)

The measurement specialist (MS) works with the utility to obtain pre- and post-retrofit utility data and identify high energy users. The MS inspects some or all jobs to insure good workmanship. As necessary, the specialist installs sub-metering and performs field studies to measure savings more precisely than utility-bill analysis. The MS reports to the EB, organizing the reports by contractor. The EB uses this data in a predetermined way to calculate semi-annual incentive payments to contractors. The measurement specialists could be independent or be employees of the EB.

Technical consultants (TCs)

Technical consultants develop standards, best practices, and complementary curriculum for various conservation options in various sectors of the market. TCs certify contractors as capable of performing work in various areas. TCs train contractors based on their contractor demand for training. Demand for training is created by a desire to qualify for approved-contractor status and to improve energy-saving performance in order to earn higher financial incentives. TCs take information from the MSs and incorporate it into contractor training.

Auditor

The auditor is responsible for verifying the independence of the players and the equitable distribution of the program’s benefits and revenues among the players. If the benefit isn’t enough for a particular player, a bottleneck may reduce the loan program’s volume. The auditor then suggests ways of increasing benefits or reducing negatives in order to eliminate the bottleneck. The auditor also reports when players are overcompensated and suggests ways of equitably reducing compensation. The auditor may audit the files of any and all players to insure compliance with program rules. The auditor performs an annual audit of the EB to determine how faithfully and how efficiently the EB is accomplishing its mission.